What Do Breeders Mean When They Say Bovine Sadness?

“Bovine sadness” is the colloquial way of referring to a group of diseases that regularly affect cattle. It is a syndrome caused by two very different microorganisms: a parasite and a bacteria. Both are transmitted through insect bites and are therefore vector diseases.

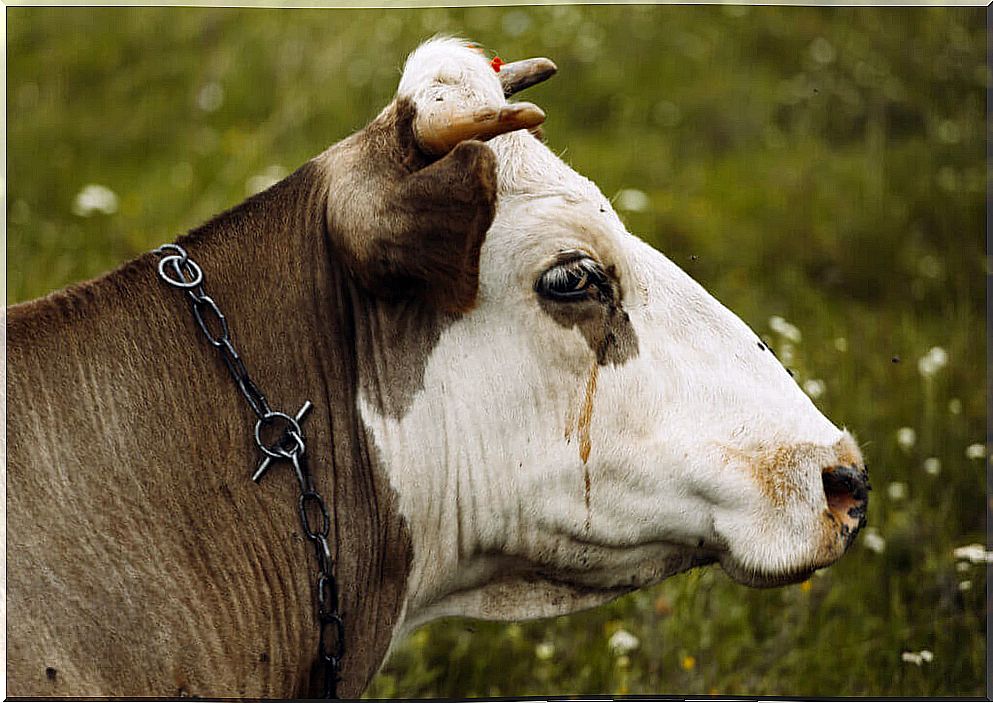

The symptoms cause a state of permanent apathy and indifference in the animal. Cows lose interest in their mates and the environment around them because of their general malaise. Therein lies the difficulty of the disease: the key point is to realize that this so-called sadness is a pathological state.

Bovine sadness, a disease that cannot go unnoticed

The term refers to two different diseases, although they share several characteristics. More specifically, breeders who talk about this syndrome are describing babesiosis and bovine anaplasmosis, whose causative agents are the following:

- Microscopic parasites of the Babesia genus .

- Gram-negative bacteria ( Anaplasma marginale) .

The growing importance of vector diseases

The incidence of vector-borne diseases continues to increase, both in animals and in humans. This is the case for most seasonal pathologies, including those we are treating in these lines.

A “bovine sadness” is transmitted through the bite of an arthropod known as tick de- Ox ( Rhipicephalus microplus) . Cases in which other hematophagous insects, such as horseflies or mosquitoes, participate in transmission have also been described.

Who usually suffers from this “bovine sadness”?

In fact, all cattle are affected by this disease, but the severity of symptoms depends on factors such as the animal’s age. Young calves, less than 12 months old, usually suffer mild infections with low mortality.

On the other hand, animals older than 2 years may have variable mortality between 20% and 50%. Thus, it will not be such a serious disease among calves, but among adult cattle.

The symptoms that give name to this very particular disease

Cows suffering from Babesia or Anaplasma infections do not show very specific symptoms. Instead, there are symptoms typical of any debilitating illness, such as fever, loss of appetite, depression, or weakness.

In lactating cows, there is a rapid drop in milk production, which shows the breeder that something is wrong. However, in beef cattle, the disease usually goes undetected until the affected animal is very weak.

The reason why these symptoms appear is the destruction of red blood cells, when invaded by any of the microorganisms mentioned. This causes hemolytic anemia (due to the rupture of these cells), which leads to the constant deterioration of the animal’s health status.

How is this disease diagnosed?

Since there are no specific symptoms, a differential diagnosis is needed with respect to many other bovine pathologies. This is so as not to confuse it, for example, with leptospirosis, botulism or bacterial anthrax. Still, there may be some suspicion when vectors are observed in the herd.

The only clinical evidence to confirm the diagnosis of “sadness” is direct observation of the microorganisms responsible for the disease. Through certain exams it is possible to observe Babesia spp. or Anaplasma spp. inside the sick animal’s red blood cells.

The final step will be to carry out the corresponding serological tests to detect the antigens or genetic material of the pathogenic microorganism. In fact, this way it will be possible to differentiate between one agent and another without the possibility of error, to proceed with the treatment.

Is “bovine sadness” treated?

As with most infectious diseases, if caught early enough, symptoms can be controlled. In this sense, first it is necessary to be sure about which organism is causing the symptoms in the animal:

- For the specific treatment of babesiosis, antiparasitic drugs, specific against these protozoa, are used.

- For the treatment of anaplasmosis, tetracyclines, which are antimicrobial drugs, are used.

The problem with both conditions is that if the diagnosis is not made in time, the damage is usually irreversible. Therefore, the best recommendation is, without a doubt, the use of vaccines.

Vaccination of cattle against babesiosis and anaplasmosis

Generally, vaccines containing red blood cells from cows infected with a pathogen whose virulence has previously been reduced are used. They are applied annually to 4 to 10 month old bovines from establishments where there are usually clinical cases.

It is also convenient to vaccinate cattle born in areas free from ticks and which will be transferred to places where they may exist. However, vaccines are contraindicated for adult animals as virulence can be reversed. Thus, the vaccine is only used in very specific cases and with conditions that are very well controlled.

“Bovine sadness” is a real challenge for South American livestock

Countries in the tropical and subtropical regions of Latin America speak of this disease as one of their greatest obstacles to raising cattle. The countless losses in the production of milk and meat, the high costs of treatment or vaccination and the high mortality caused by cattle sadness do not give the breeders any respite.